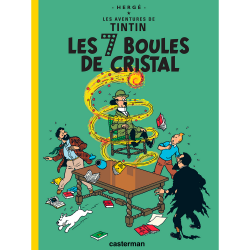

Hergé, a driven perfectionist prone to bouts of exhaustion and depression, was getting ever more ambitious in the scope, subject and composition of Tintin’s escapades. The books, or “albums,” that collected his adventures had become enormously popular the series arguably hit its iconic peak in the 1940s with a pair of two-volume adventures - the piratical treasure hunt of The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure, and the mystical Aztec odyssey of The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun - that would greatly influence the creation of Indiana Jones. Tintin’s strip had moved from the pages of a Belgian newspaper to his own magazine, where it was published in full color. In the 1930s, The Blue Lotus took Tintin to China in the midst of Manchuria’s invasion by Japan, while King Ottakar’s Scepter foreshadowed the start of World War II as Tintin helped defend Syldavia, a fictional Balkan state, against the expansionism of its fascist neighbor, Borduria.īut by the mid-’50s, both Tintin and Hergé were in a different place. Unlike most other comic strip heroes of the mid-20th century, Tintin operated in a world based in geopolitical reality he was ostensibly a journalist, after all, and his creator, the Belgian artist Hergé, loved to take inspiration from the headlines. This wasn’t entirely new ground for Tintin. In The Calculus Affair’s Cold War, confusion reigns, and allies aren’t what they seem. It would take him into the heart of the Cold War, and embroil him in a secret struggle for the plans to a deadly superweapon. In December 1954, the boy reporter Tintin embarked on an adventure that had all the hallmarks of a classic spy thriller: The Calculus Affair. It wasn’t until the early 1960s, when Bond broke into cinemas and The Man from UNCLE hit TV screens, that spies became cool, and the nuclear-powered struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union started to be truly mined for mass entertainment.īut one clean-cut pop-culture hero didn’t waste time diving into this conflict, and he did it in the pages of a French-language magazine for kids. Ian Fleming had published the first James Bond novel a year prior, but in postwar film and TV, producers were mostly looking for escapist entertainments and historical epics that got as far from the political zeitgeist as possible.

Polygon is diving into the world of espionage throughout fiction and pop culture history with Deep Cover, a two-week special issue covering all sorts of spy stories and gadgets.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)